Design thinking has revolutionised the creative industry.

Here’s how IKEM is using the process to reimagine communication around gender equality in the workplace.

The project began on a train.

With the open fields of northern Germany racing past the windows, women sat together and spoke in hushed tones about the conference they had just left.

It had not gone entirely as expected.

One woman said a man at the conference had asked her to take notes while he and the other men conversed about issues like the electrical grid and wind turbines – issues she had come to discuss. Another woman, who was at the conference to discuss the prospects of wind energy, had been instructed by men at the conference to clear dishes after attendees had finished lunch.

Quick navigation

A third woman had been groped at one of the networking events.

And all of the women had gritted their teeth when they saw the restroom doors in the hotel lobby, which distinguished the women’s restroom from the men’s by a single word inside a painted thought bubble: ‘Shopping’ for women, ‘Football’ for men.

As the women talked, a common thread quickly emerged: none of the women were satisfied with their response to these situations. Various options had raced through their minds, but they’d hesitated too long – reluctant to make a scene, to accuse someone of something, to alienate fellow professionals in their field.

The women – all IKEM employees – marvelled that this had gone on at a conference on climate change, a research area that seemed more likely than others to attract advocates of wide-ranging progressive policy, including policies to advance gender equality. If all of this could happen there, they asked each other, what went on at conferences in other fields?

And: what if they could change it?

By the time the train slowed to a stop in the Berlin station, they had developed plans for a toolkit that would shine a light on experiences like these, encourage women to share their own stories and discuss empowering responses, and supply facts and figures to build strong arguments for gender equality.

Quelle: Ellery Studio

Quelle: Ellery Studio Anika Nicolaas Ponder, head of the Sustainability & Innovation Department at IKEM and one of the initiators of the project, pitched the idea to the designers at Ellery Studio, who were immediately enthusiastic about the concept. A team quickly assembled around the effort and grew to include artists, engineers, social scientists, copywriters, translators and others from more than seven countries.

Design thinking

The team developed the toolkit using a procedure called design thinking, an iterative approach to product creation that integrates end-users directly into the development process, drawing on their input to align the product as precisely as possible with their needs. This creates a collaborative environment that implodes the traditional hierarchies of the design process, placing end-users – not product developers – at the centre of the creative process.

Design thinking is credited with inspiring creative breakthroughs at some of the most innovative companies of the past decades, including Apple and Microsoft, and Ellery Studio regularly employs the process in its workflow.

Quelle: Ellery Studio

Quelle: Ellery Studio Bernd Riedel, head of creative strategy and design at Ellery Studio, described the approach as a ‘formal version of a functional design process, represented in a way that makes that process accessible to people who are not necessarily in the design world.’ The design thinking process is useful in creative industries, he said, because it offers an orderly approach to ‘move from your goals to what you want to do and how you want to do it – and how to actually get stuff done. It can bring structure into this universe of wild creativity.’

The approach was a natural fit for the development of the EQT toolkit, Riedel explained, because the idea for the project originated with people working outside of the design field. ‘The process was co-creative from the beginning,’ he said.

Riedel, who has been involved in the development of the EQT toolkit since the earliest brainstorming sessions, said the procedure was also especially appropriate for the project because it allowed the team to avoid reproducing, in the design process itself, the dynamics that the toolkit was designed to address: the methodology cultivated an environment of collaboration that centred product development around the needs of women and their allies.

‘We wanted to avoid acting like we were the gatekeepers of the information, especially for women as a community,’ he said.

Quelle: IKEM

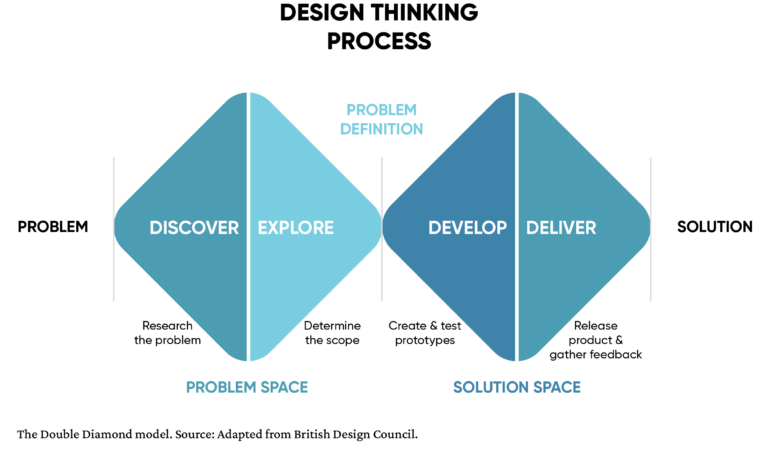

Quelle: IKEM Design thinking methodology remained relatively amorphous until the British Design Council introduced the Double Diamond framework in 2004, formalising the process. The framework presents a kind of map for product development, presenting the methodology as a series of four steps.

The steps are visualised as two adjoining diamonds, the first representing the ‘problem space’ and the second representing the ‘solution space’. Each of these spaces, in turn, represents two steps in the design process: the problem space consists of the first two steps of the process, Discover and Define, while the solution space is composed of the final steps, Develop and Deliver.

But in the design thinking process, the work doesn’t end when the product is delivered. After releasing the final product, design teams continue to gather input so that they can refine the product and improve its quality – a feedback loop that, with each iteration, yields a product that better meets the needs of end-users.

For the team creating EQT, the steps outlined in the Double Diamond framework would set the course for the development process.

Quelle: Ellery Studio

Quelle: Ellery Studio  Quelle: Ellery Studio

Quelle: Ellery Studio Step 1: Discover

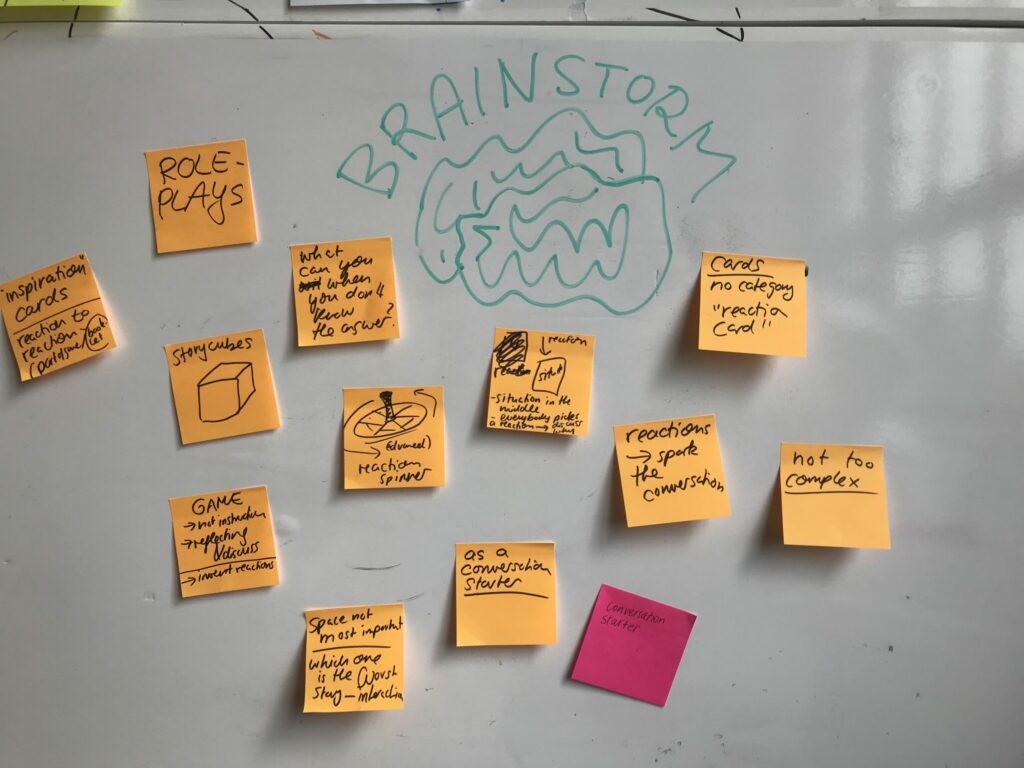

In the first phase, Discover, design teams explore a challenge from all angles through desk research and brainstorming sessions, as well as field research, including interviews. In brainstorming sessions, nothing is off limits: the goal is to gather as many unfiltered ideas as possible. The team jots ideas on sticky notes and posts them on the walls of the meeting space, creating an ever-growing patchwork of coloured paper that allows team members to visualise connections between individual ideas.

Nicolaas Ponder said the success of the design thinking approach depends on the ability of those involved in the process to adopt the ‘neutral perspective of an alien’ – especially in the Discover phase.

‘You really kind of need this kind of professional naivety to see things from a fresh perspective and then design them better,’ she said. ‘We try to take a problem or a challenge or process that needs improvement, and then ask questions – for example: are we stuck in old systems? How can we rethink an approach, redesign it and implement it? We imagine what could be, and then design towards it.’

Quelle: Ellery Studio

Quelle: Ellery Studio In this first phase of toolkit development, one of the team’s major focuses was on field research. Odile Stabon, who served as lead designer for the toolkit’s infographic poster, collaborated with illustrator Sheree Domingo to interview 15 women about their experiences with sexism at work. After each interview, Stabon and Domingo carefully documented what they had heard, making a note of each woman’s profession. They spoke with women from a range of fields, from tattoo artists to waiters and engineers.

‘I was surprised to find out that so many women were going through similar situations in their career paths,’ Stabon said. ‘Not a single woman we interviewed said, “Oh, I don’t have any experience with sexism at work.”’

Stabon, who now works at IKEM as a graphic designer, had begun work on EQT directly after taking a position at Ellery Studio. ‘The interviews for the toolkit were a really valuable opportunity for me personally,’ she said. ‘As I was starting my career, I was learning about scenarios that might come up at work and finding out how to put names to problematic situations that I may already have witnessed without even noticing they were wrong.’

Quelle: IKEM

Quelle: IKEM Louise Camier, who began analysing background information for the toolkit as a working student at IKEM, said she was surprised by much of what she learned from the research – such as the persistence of the gender pay gap despite laws prohibiting gender-based wage discrimination – and was taken aback by how recent much of the progress on women’s rights had been.

‘I was shocked that so many of the opportunities that we take for granted today actually only opened up relatively recently,’ she said.

By the time the Discover phase was complete, Camier and other researchers had compiled statistics, facts and figures into a sprawling document that would be reviewed and organised in the following phase.

Step 2: Define

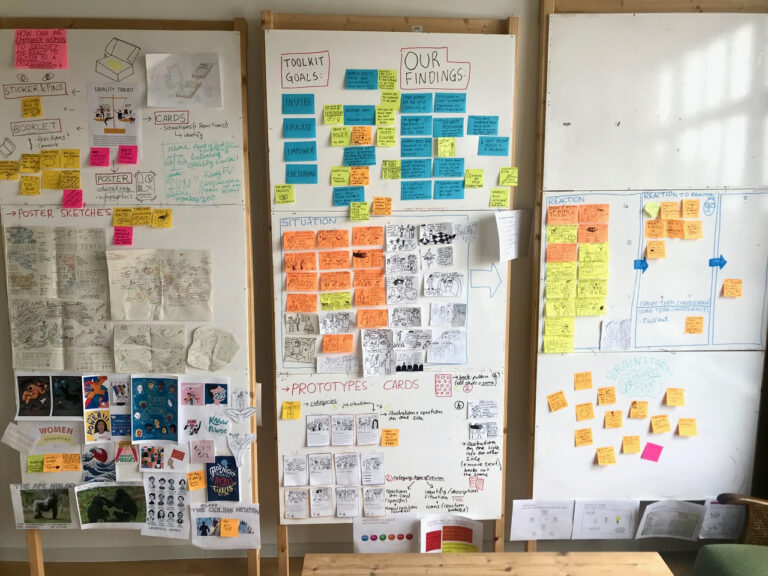

In the Define step, the design team sifts through the ideas, analysing data compiled from their earlier research and identifying the common threads that emerged from interviews. The goal is to identify root causes of the problem, which will guide their efforts in the next phase of the process: product development.

The team reviewed notes gathered from the interviews and from desk research. In the interviews, women had reported that their encounters with sexism at work left them feeling disempowered. They tended to fault themselves for the situation – in many cases because they believed they must be to blame for the situation, and in nearly every case because they felt that they had not responded effectively in the moment.

The anecdotal evidence from the interviews was borne out by a ream of research publications that established gender inequality as a persistent problem in workplaces around the world, including in Western Europe.

After analysing their research, the team defined a direction for the project. ‘We developed an initial question,’ Stabon said, ‘which was: how can we empower women to recognise and respond to sexism in the workplace? Then we created the different elements of the toolkit as a response.’

Quelle: Ellery Studio

Quelle: Ellery Studio But determining the problems that the toolkit could address meant determining the problems it could not address. That made the Define stage one of the most difficult aspects of the toolkit’s development.

‘Our team wanted to do justice to all of the social inequalities that shouldn’t even be an issue in 2022,’ said Nicolaas Ponder, describing the team’s deliberation over the direction of the project as ‘a long process.’

‘For the sake of creating a product that is targeted, is effective, can appeal to a lot of different people, and can be produced on time, we decided that, for now, we would focus mostly on the issue of gender equality in the workplace, mainly for women and femme-identifying folks,’ she said.

After considering different options, the design team decided that an infographic poster, an informative handbook and an illustrated card game could achieve multiple goals.

Quelle: Ellery Studio

Quelle: Ellery Studio In the interviews, women had reported feeling reluctant to initiate conversations about gender equality for a range of reasons – because the topic seemed too complex to untangle in casual conversation, for example, or because they were wary of voicing a perspective that was likely to meet with deeply entrenched opposition, or because they didn’t want to risk deflating the mood of a social gathering.

Using comics-style illustrations in every element of the toolkit keep the tone of the topic light, the team decided. That could lower barriers to engagement enough that people would actually want to learn about the issue and join in conversations on the topic.

The team reasoned that women and their allies would feel more empowered to recognise and respond to sexist situations in the moment if they had a ready supply of facts and figures, as well as a detailed understanding of gender inequality in the workplace. The poster and handbook could provide access to facts and historical background on gender inequality, enabling women to situate their own experiences within a broader social context – and potentially reducing the likelihood that they would interpret sexist encounters as something they had somehow brought upon themselves.

Quelle: IKEM

Quelle: IKEM To address the perception that a conversation on gender equality was too complex to address, the card game would offer a manageable solution: the goal would not be to find one sweeping solution to gender inequality, but to address gender inequality as it manifests itself in daily life – as a series of individual interactions between women and colleagues, employers, casual acquaintances and others. The format of the game would spark dialogue and prompt players to weigh many possible responses to a single situation.

‘What came up a lot in the interviews was that when these sexist situations happened in the workplace, women were shocked and didn’t know how to react in the moment, then later felt guilty that they hadn’t done anything about it,’ Stabon said.

The card game was designed to counteract this effect. ‘The benefit of the card game is that it allows you to see these scenarios illustrated and role-play how they might play out,’ she said. ‘Then, when the situation arises in real life, you can quickly find a way to react.’

Once the team had defined the direction of the project, they began to focus on developing each individual component.

Step 3: Develop

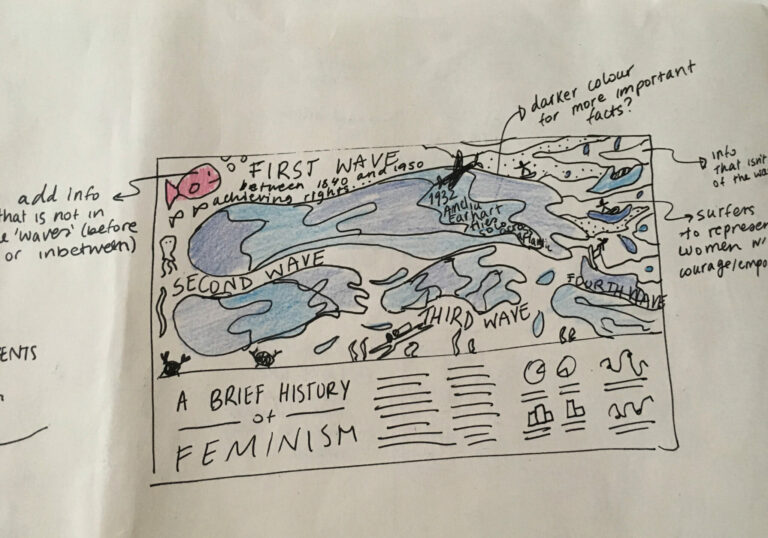

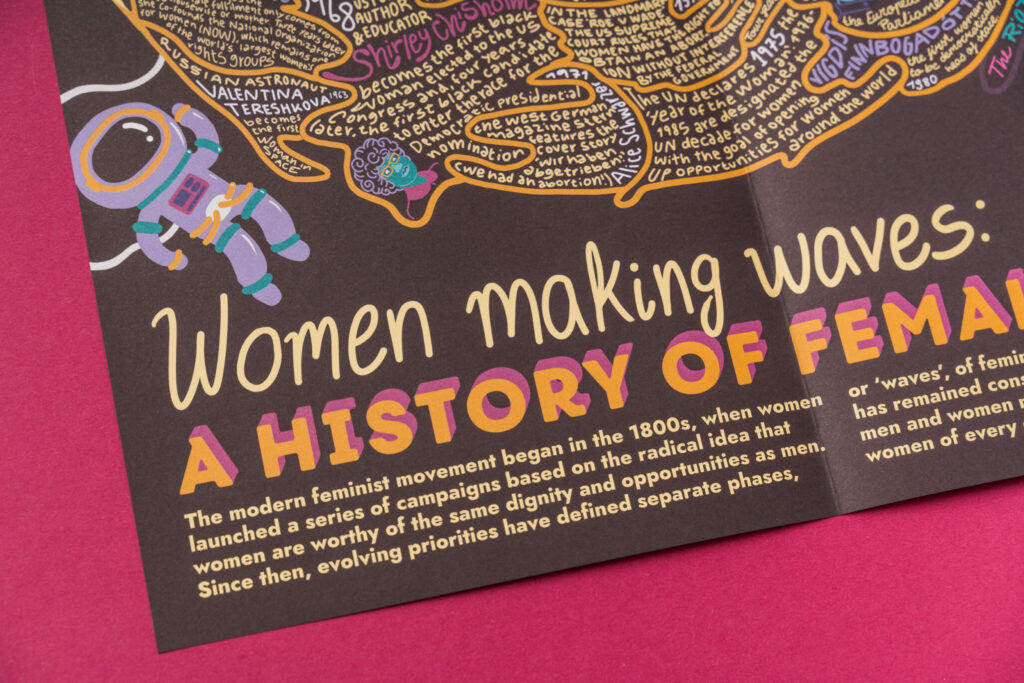

The first product developed for the EQT toolkit was an infographic poster.

‘The idea of having a poster came from our research,’ Stabon said, ‘because we found that there’s not enough knowledge out there. So we did more research and read about the history of feminism and collected information on women from the past, and decided we could put out an information piece showing how all of these women behind us have paved the way.’

The team’s research showed that, if progress continues at its current rate, the gender gap in the EU won’t close for another 61 years. In North America, full gender equality will take even longer: a staggering 168 years. A poster chronicling the achievements of the past 150 years could give women – and their allies – hope that continued progress is possible, the team reasoned, despite persistent problems like the gender pay gap. The team included these and other statistics in infographics on the front and back of the poster.

Quelle: Ellery Studio

Quelle: Ellery Studio On the front of the poster, Stabon sketched a timeline composed of four foam-capped waves, representing the ‘waves’ of feminism. Each wave consists of a patchwork of hand-lettered summaries of individual milestones, illustrated by Ellery artists Domingo, Lucía Cordero and Hannah Rasper. The timeline stretches from 1848 – the year of the first women’s rights convention – to the present day.

In 2018, the finished piece, titled ‘Women making waves: a brief history of female empowerment,’ won the Equality and Woman’s Promotion Main Award in the print category at the Malofiej International Infographics Awards.

Quelle: Ellery Studio

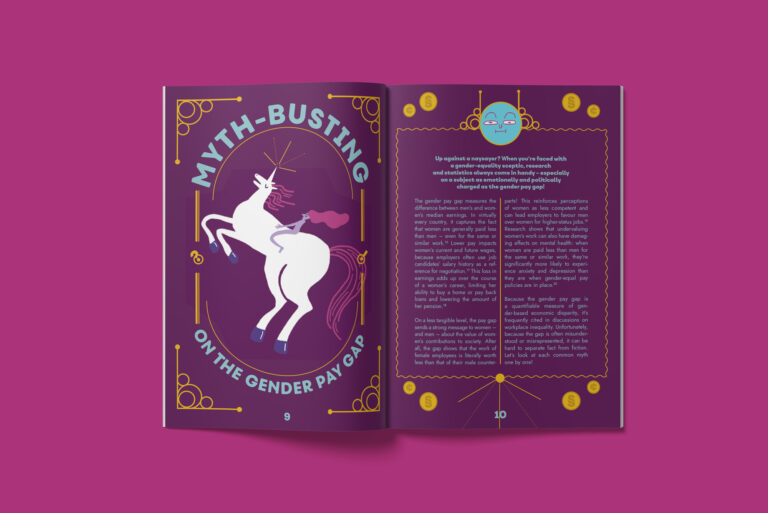

Quelle: Ellery Studio After the handbook text was complete, artists and designers at Ellery – including Gaja Vičič and Hannah Schrage, in addition to Domingo and Cordero – began work on illustrations and formatting. In the handbook, the text and illustration combine to present the content in a creative way: one chapter explains common barriers to women’s career advancement by representing the ‘glass ceiling’, ‘sticky floor’ and other concepts as a series of traps hampering progress through the darkened corridors of a haunted house.

Quelle: Ellery Studio

Quelle: Ellery Studio Meanwhile, the IKEM-led research team – which included Nicolaas Ponder, Steinkraus and Camier as well as Kate Miller and Dàmir Belltheus Avdič – analysed reports and other available materials on gender inequality, then compiled their findings into a 46-page companion booklet. The handbook presents key findings and compelling arguments that can form the building blocks of a productive discussion on gender equality.

The text breaks content down into eight chapters, each covering a specific aspect of gender inequality. One chapter, for example, debunks common myths on the gender pay gap, from ‘There is no gender pay gap’ to ‘Women earn less because men are better at negotiating higher salaries’. The title of the handbook, Gender equality: all aboard!, refers to the toolkit’s objective – to inspire women and their allies to unite behind gender equality – as well as to the train ride that set the project in motion.

To create the game, the team combed through the earlier interviews, condensed each scenario into a few lines of punchy text and developed a title for each that included creative wordplay. After creating 50 of these Situation cards, the team developed another 50 Reaction cards and added two jokers, then illustrated each of the 102 cards in the style of a colourful comic.

Alex Steinkraus, who began to work on the toolkit soon after joining IKEM in 2019, views the card game as a unique aspect of the toolkit. ‘It allows EQT to be more than something that was only built to be read and consumed,’ she said. ‘With the card game, we were able to make it interactive – something that people can actually try out and have conversations about.’

The comic-style graphics and humorous text make the game playful – but it doesn’t hand players easy answers. Instead, it provides them with a framework for what Stabon refers to as ‘guided solutions’.

‘The card game is an active exercise that leads you, in a playful way, to kind of find your own solutions,’ she said.

Quelle: Ellery Studio

Quelle: Ellery Studio The team designed the game to inspire constructive conversations that would encourage women to share their own experiences of sexism and discuss possible ways to respond to future scenarios.

‘In the course of the project, we very quickly realised that every woman or femme-presenting person has their fair share of these experiences,’ Riedel said. ‘That’s why, in the role-play game, we give a lot of exposure to different scenarios and create the conditions for people to be able to exchange opinions and share their thoughts.’

These exchanges were also incorporated into the game to address one of the problems the team had identified in their interviews on sexism at work: women blamed themselves for the situations and kept their stories to themselves, which often prevented them from gaining the confidence to take action.

‘That feeling of isolation is also very important to address and to change,’ said Nicolaas Ponder. ‘That’s why the game is a kind of community-building exercise. It leads you to connect with your peers and makes it clear that is a real-life thing and you’re not the only one going through it.’

Quelle: Ellery Studio

Quelle: Ellery Studio Players bring their own histories to the game, which shape the conversations that develop around each situation and reaction. This makes the card game more inclusive, Stabon said, because ‘it puts users at the centre of the experience and gives them visual cues to inspire conversations led by their own values, perceptions and opinions.’

It also means that the game can offer a fundamentally different experience every time it is played, depending on the specific players taking part.

In the prototyping phase of the project, the team hosted a series of workshops at the studio, where they divided participants into small groups, handed out prototypes of the cards and then gathered feedback on users’ experience with the game. Following these ‘beta tests’, the team met internally to discuss how to implement the feedback they had received.

In some cases, this meant throwing out certain cards and creating new ones, or tweaking the wording of the text. The team worked extensively on the titles of the cards in order to strike the right tone for the English and German versions of the game – a major undertaking, they found, considering that the wordplay could seldom be translated directly from one language to another.

Quelle: Ellery Studio

Quelle: Ellery Studio In the feedback sessions, some participants said they were embarrassed to find that certain Situation cards reminded them of something they had said or done in real life, without realising at the time how it had come across.

Others expressed scepticism that the scenarios portrayed on the Situation cards would occur in real life, arguing that some of the behaviour was too extreme to be realistic.

‘I noticed that a lot of people saw the cards and said, “Oh, my gosh, does that even happen?”’ Nicolaas Ponder said.

The team could respond by referring to the interviews conducted in the Discover phase, which provided the material for the scenarios. ‘All of these situations have been carved out of those interviews, done with so many different people from all walks of life and industries and jobs. These situations are all based on real life experiences,’ she said. So we can say, wholeheartedly, “Yes, this does happen.”’

Based on input from workshop participants, the team fine-tuned the toolkit. They added several blank cards to each deck, for example, making it possible for players to supplement the existing cards with a scenario drawn from their own lives.

Quelle: Ellery Studio

Quelle: Ellery Studio Steinkraus views the workshops as a key step in the creation of the toolkit. By integrating workshop participants into the process of developing and fine-tuning the toolkit, she said, ‘we were able to talk to a lot of different women from a lot of different backgrounds and make sure that co-creation was really a centrepiece of the toolkit.’

This was essential to the team’s process, she explained, because each participant contributed expertise that played an important role in the project’s creation.

‘While we can’t speak for everyone, workshopping allowed us to incorporate as many different voices – as many different perspectives from women in all different kinds of workplaces – as possible,’ she said. ‘And I don’t think that that inclusivity would have been possible without something like design thinking and this workshop co-creation approach.’

Quelle: Ellery Studio

Quelle: Ellery Studio Step 4: Deliver

With the prototypes complete, the team turned their attention to delivery. They began to prepare for a crowdfunding campaign – an essential step in funding the production of the final product. The EQT Kickstarter campaign, which launched on 19 May, aims to raise €9,900 by 3 July to begin the manufacturing process.

Even before the campaign got underway, the team had begun fielding requests for workshops that were based on the toolkit. In early 2022, for example, Stabon, Nicolaas Ponder, Steinkraus and Camier shared insights from the toolkit development process with representatives of Ukrainian women’s rights organisations.

The workshop, which was organised by Cultural Vistas, was ‘a great experience,’ Nicolaas Ponder said. ‘In our presentation, we were very honest about our experience, about the fact that, before we began this journey of creating the toolkit, we had not necessarily known that certain things we encountered were based on gender bias or sexism or inequality.’

She was pleased with the results of the workshop: participants were enthusiastic about the potential for the toolkit to spur positive change. ‘We got so much positive feedback,’ she said.

The team plans to offer additional kinds of workshops focussing on different aspects of gender equality. Some workshops can explore ways for employers to tap into additional employee brainpower and increase worker satisfaction by implementing gender-equal practices in the workplace. Nicolaas Ponder also hopes to create workshops that draw on IKEM’s expertise in sustainability to examine the intersection between gender equality and climate change.

Riedel said the game can be played in workplace trainings as well as at casual meetups – which offers many opportunities for it to drive change. ‘There are so many settings where you can use the toolkit to explore this topic and see what happens,’ he said. ‘We’ve already had a lot of events where people have been really intrigued to try it out, especially in progressive conference formats.’

‘I think the toolkit has the potential to be part of a grassroots effort to improve lives, at work and beyond,’ added Camier.

For the creators themselves, the toolkit has already had an impact.

Riedel observed this impact firsthand. ‘I could see the development of a lot of personal growth among the people in my team,’ he said. ‘Through their work on the project, the team gained a lot of background knowledge and deepened their understanding of the topic. And being exposed to that through the project really emboldened them, which was amazing to see.’

Stabon sensed that change in herself. ‘Before I started to work on the toolkit, I didn’t really feel close to the world of feminism,’ she said. ‘Working on the toolkit and meeting so many talented people along the way was a real eye-opening experience. I learned that so many women before me had paved the way to create the opportunities I have today as a young professional.’

Quelle: IKEM

Quelle: IKEM For his part, Riedel hopes that the toolkit will inspire others to develop innovative formats to address other inequalities. ‘Our goal is for other people to see the concept, understand it, and then start to be able to imagine similarly creative approaches to other issues as well. We want to encourage people to cross these mental borders that they might set for themselves,’ he said.

The toolkit can have a far-reaching impact, Steinkraus said, because it equips women and their allies to advocate gender equality in so many different ways.

‘You can use the toolkit to arm yourselves with the facts, learn more about the issues and practise your reactions. This combination of elements really makes it possible to find your voice,’ she said.

This step-by-step approach is essential to initiate sustainable change, said Steinkraus. ‘In this toolkit, we’re looking at the workplace specifically. We’re looking at things that we can start to advocate for as individuals, from one day to the next. And I think that’s a starting point for a lot of people, and it addresses something really important.’

But Steinkraus sees this as only one step in a longer process – a process which, like the development of the toolkit itself, can only be successful with effective collaboration.

‘As with any inequality in society, it’s never going to be up to one group to drive change. We need those who have power to do something about it,’ she said. ‘We need everyone on board. Everyone needs to be part of the conversation and act as allies to drive change.’

The EQT fundraising campaign ends on 3 July! Visit the team’s campaign page on Kickstarter to preorder a copy of the toolkit, donate to the campaign, and select rewards ranging from tote bags to a custom gender equality workshop facilitated by IKEM and Ellery Studio.